Neither Northern nor Southern

Centre College During the

Antebellum Era and the Civil War

By Laura Garrett

Slaves at Centre

|

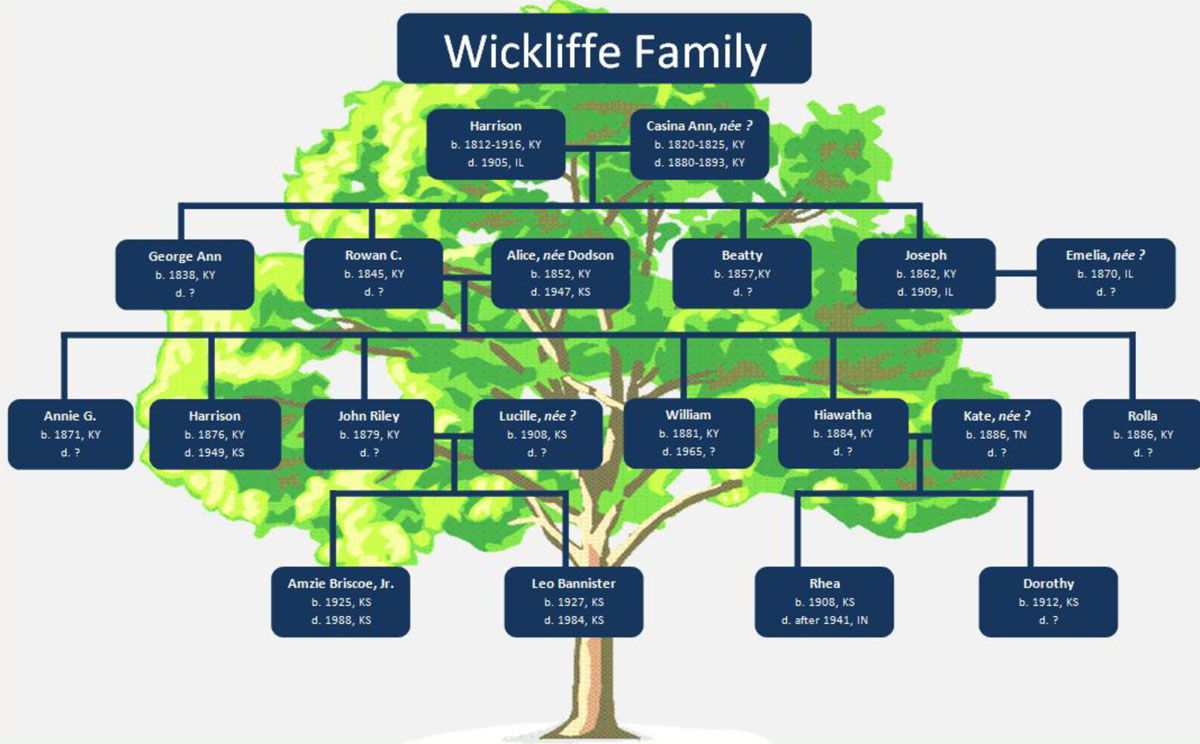

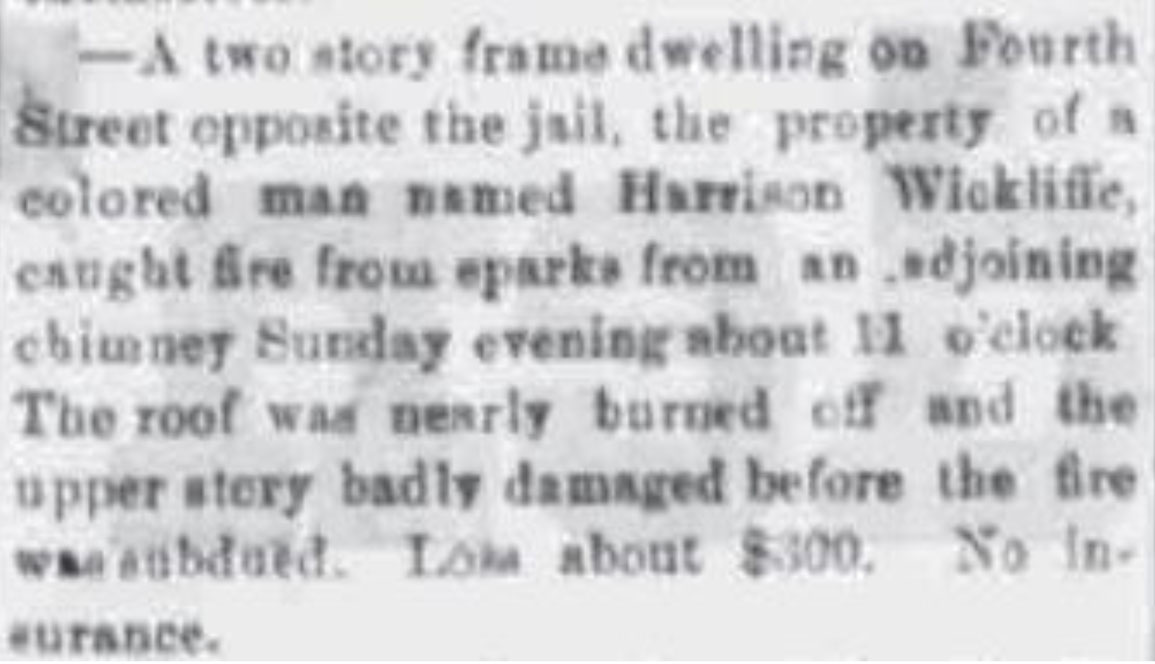

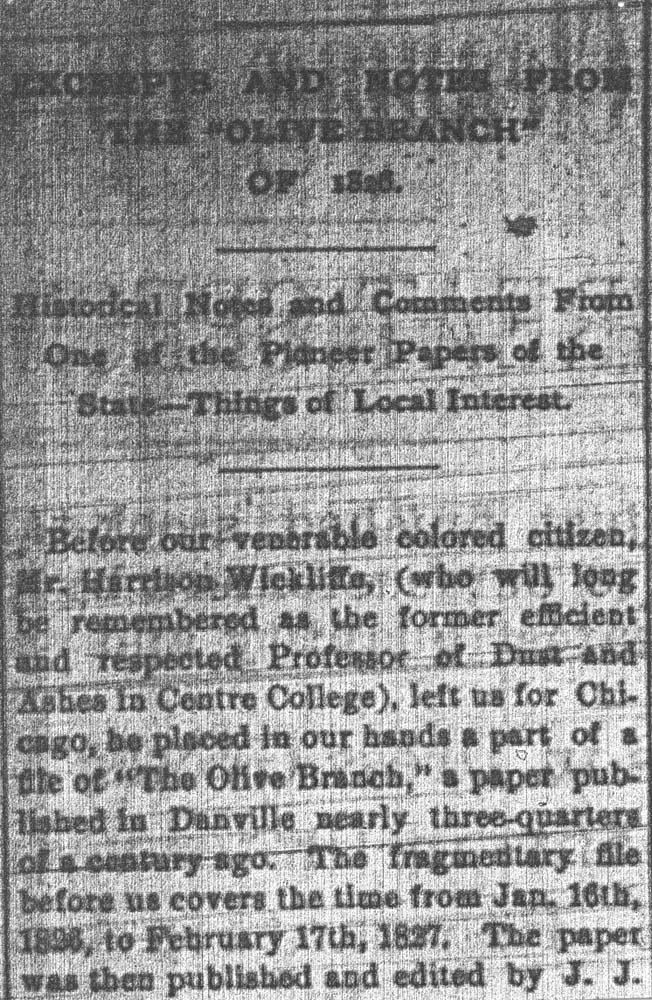

Centre never owned slaves, but did use slaves by hiring them from their owners. Slaves are twice mentioned in a student newspaper created in 1864, and although it is unclear whether these were slaves who worked at Centre or elsewhere, their mention demonstrates the familiarity that Centre students had with slaves while in school1. Financial ledgers from 1824 through 1853 show that Centre hired slaves from the Cowan family and Centre president Gideon Blackburn on a task-by-task basis to do chores such as chopping wood, washing, and janitorial services. Slaves were also hired from their masters to work full-time at the school. One man who did such work was Harrison Wickliffe, a Kentuckian who was born a slave but was a free man by middle age. Harrison was born between 1812 and 1816, likely under the ownership of U.S. Representative Charles A. Wickliffe, of Lexington. He was sold to the Crittenden family at a young age, and came to be owned by Centre president John C. Young when Young married Cornelia Crittenden in 18392. Young rented Harrison to the college to work as a janitor and groundskeeper, but by 1850, Young had apparently set Harrison free as he did others of his slaves. After gaining his freedom, Harrison, his wife Casina, and their children Beatty, Joseph, and George Ann continued to live in a house that they rented from the college. Meanwhile Harrison's oldest son, Rowan, enlisted in the 55th Massachusetts Colored Infantry as a boatman in 1863, and was eventually promoted to full corporal. Harrison continued working as a janitor and painter at Centre for an annual salary of $150 until 1870. He then became self-employed as a house painter while his sons Beatty and Joseph worked as hotel waiters, perhaps at the Gilcher Hotel, where the Hub Coffee House now stands. In January 1893, a widower at age 81, Harrison moved to Chicago to live with Joseph and Joseph's wife, a white woman named Amelia. Harrison died in 1905.

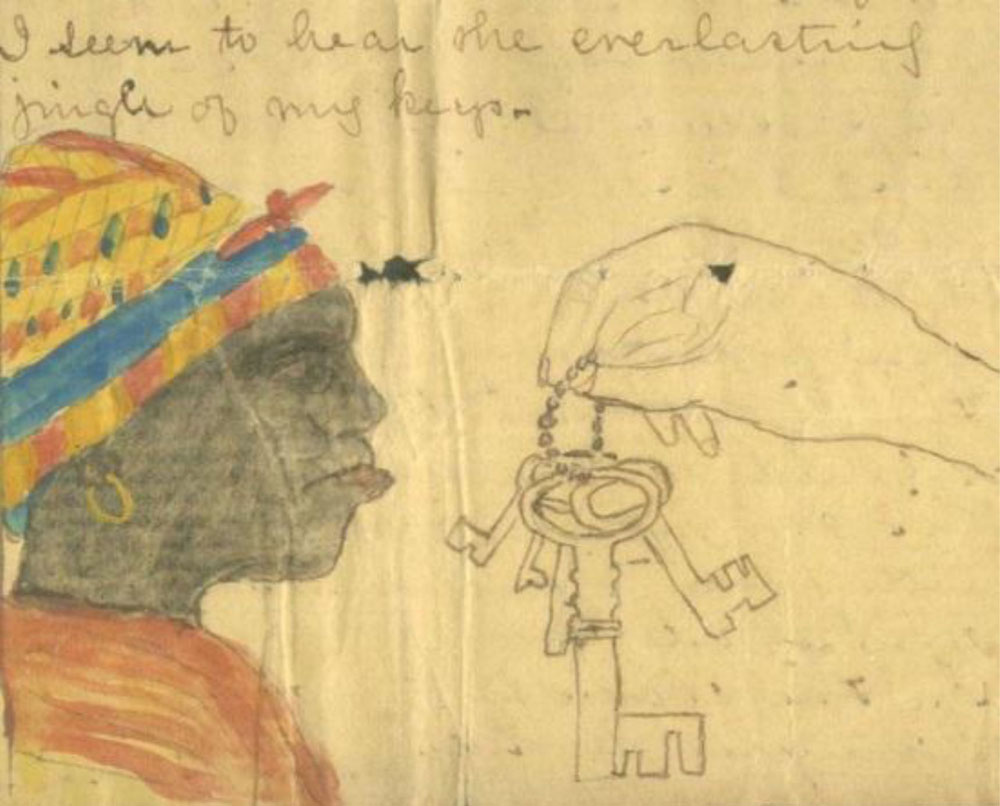

1 The student newspaper was "Hoots from the Pine Woods Owl," written in December 1864. The two stories of African American slaves are of "Ben the Ethiope," who was attacked while delivering a basket of food at the request of Centre students, and an unnamed woman who writes about being distracted by the other servants (it is not entirely clear that she was a slave). |