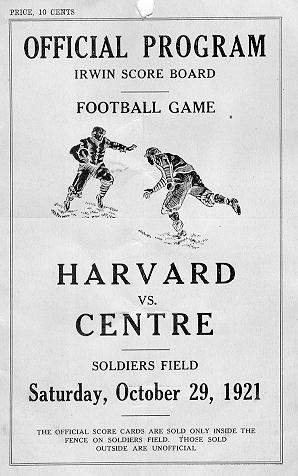

As practically anyone who grew up in Kentucky knows, the Centre College football team defeated Harvard in 1921 by a score of six to nothing. In losing to the smallest college it had ever played, Harvard suffered its first intersectional defeat in four decades. Coming as it did at a time in which football was the most outstanding spectator sport in the nation, the game had such an impact on the sporting world that in 1950 the Associated Press named it the upset of the half century. For one glorious moment Centre College was, as the New York Times noted, catapulted into the center of the football universe.

Not surprisingly, Kentuckians made outlandish claims about their team. "In every nook and cranny of the universe where deeds of mighty men of Caucasian races are recited, its achievements are known," trumpeted the Louisville Herald. The Lexington Herald contented itself with the observation that the Colonels were, in many respects, the greatest football team the world had ever known. The Danville Advocate, mourning that no worlds remained to be conquered, was even less restrained. "CENTRE WINS," the headlines screamed. "McMillin, The Hero of the Football World, President of the United States for Time Being. He Is The Great Effulgent Star." As for the work of the team's linemen, the paper's delirious congratulations knew no limits: "The Line! The Impregnable Line! Held The Bridge, So Harvard's Mightiest Could Not Cross It - The Line, The Line, Drink Hardy, The Line! - God Bless The Line!... God Bless Our Team, each and all of them."

Perhaps even more astonishing than the compliments its worshipful fans paid the team was the fact that much of what was said also happened to be true. George Trevor of the New York Sun has aptly remarked that the Centre-Harvard game was perhaps the most romantic chapter of America's gridiron annals. As he noted, the story - "an unbeatable combination of sure-fire wow, the more gripping because they were founded on fact, and not trumped up by publicity agents" - had all the elements necessary to create a legend. The Centre-Harvard game needed no mythical embellishments. The history of the 1921 Centre team was just as colorful and unbelievable as any fantasy or tall tale that has emerged as part of the lore surrounding the team.

Indeed, the closer we come to the facts of the matter, the more it is apparent that seemingly impossible images - of a team that prayed and cried together; of a star quarterback who earned his way through college by gambling; of a coach who brought a belt to practice to encourage stragglers and who then stayed after practice to repair uniforms; of a town that went absolutely berserk when its team won the big game - were all at one time quite real. The Praying Colonels of 1921 were the kind of team about which legends are made, but the team itself was just as remarkable as any legend ever was or could be.

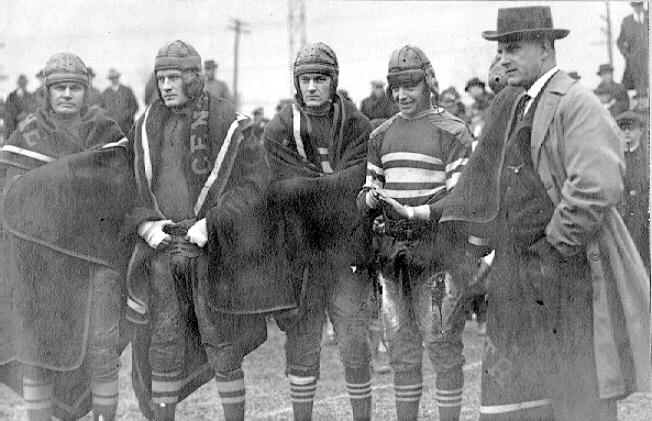

It was a combination of good fortune, hard work, talented players, and inspired coaching that produced a team of championship caliber. Robert "Chief" Myers, a Centre graduate who coached high school football in Fort Worth, Texas, was the catalyst. Some stories claim that Myers first encountered future quarterback Alvin Nugent McMillin (known as "Bo" to his fans and "Nuge" to his friends) when the boy was being chased by police after trying to sneak into a Fort Worth baseball game. Less dramatic accounts argue that Bo quit school at age 12 to support his family, and that Myers discovered him when he substituted for a missing player on his brother's football team. In any case, Myers took the boy under his wing, teaching him how to play football and telling him stories of a marvelous school in Kentucky named Centre College. Eventually Bo, "Red" Weaver, and Thad McDonald left Fort Worth for Somerset, Kentucky, recruited by boosters of Somerset High School. At Somerset they played with native Kentuckian "Red" Roberts, a rambunctious future All-American with red hair who, because he wore no helmet, was always instantly recognizable on the field. The Somerset football team was dazzling, and the prospects for Centre when the Somerset graduates were admitted were no less promising. Eventually more Texans - Matty Bell, Sully Montgomery, Bill James, and Bob Mathias - enrolled at Centre as well. Myers, who had returned to Centre to coach the team, realized that he was dealing with superior athletes. Without their knowledge and against their later protests, he went in search of a coach who could do the team justice. He found his man in "Uncle Charlie" Moran, a no-nonsense National League umpire who had stopped by Danville after the baseball season to watch his son play football. Moran's qualifications were impressive: he had played college and professional football, had assisted at Carlisle when Jim Thorpe was playing there, and had coached Texas A&M. At the players' insistence, Myers stayed to help, occupying the position of athletic director.

The two men were rigid disciplinarians. Colonel George Chinn, a lineman for the team, remembered vividly that Moran brought a belt to practice and used it whenever and wherever he thought it was needed. Curfew hours were strictly enforced, and though drinking was, according to Colonel Chinn, not completely banned, none of the boys found themselves able to indulge and still run the three miles required before every practice. In addition to their coaching duties, Myers and Moran served as the team's trainers, tailors, and cobblers. The College had little money to spend on athletics, and all resources had to be carefully husbanded. Players who tore their uniforms in a game realized that no new ones were forthcoming; the old ones would simply have to be repaired. Billy Reed, writing for Sports Illustrated, reported that before the Harvard game the team's jerseys had become so shredded that Moran finally went out on his own initiative and bought plain white tops at a rummage sale. His wife and a few other Danville women dyed the jerseys gold and painted white stripes on them so that, as Bo graphically stated, "we could look respectable like while we whaled the stuffin' out of our opponents."

Stringent as the conditions under which the team played may have been, the players responded enthusiastically. As Bo wrote after the Harvard game, spirit, "which makes every man on the field outdo anything he ever realized he had in him," was the key to the team's success. The team regularly prayed together before every game, and it was not at all unusual for the players to be so moved that they ran onto the field in tears. Bo, who admittedly financed his education by his gambling skills, was in every other respect a devout Catholic. Norris Armstrong, the 1921 captain, attested that Bo never swore or drank. The moral tone of the rest of the team was equally high. "If you had thirty-two teeth and you only wanted four," emphasized Colonel Chinn, "all you had to do was go in that locker room and cuss."

Moreover, Moran and Myers were able to instill in the team the feeling that they were fighting for something larger than themselves: for each other and for the glory of Centre. As Myers wrote of the team in the summer of 1921, "brotherly love and team-spirit 'made' us, more than anything else .... The older I get, and the more I see of other institutions, the better I appreciate Centre. When you become a Centre man, you confer a sort of knighthood upon yourself and become in a sense a man apart from the rest." The 1922 college yearbook echoed this sentiment, explaining that the team's outstanding record was made "still more wonderful by the college from which it came and whose sons know nothing but undying loyalty."

In their team prayers, the players did not pray for victory; rather, they humbly asked that "we might fight like men to the last ditch, and live up to the traditions of Old Centre." The College students and the town of Danville were unsparing in their support for the team, and the players were ever conscious of their fans' loyalty and their coaches' wholehearted devotion. As Bo put it, everyone on the team knew "that the college is behind us to the last ditch, and that the city of Danville looks upon us as its own adopted children. Moreover, we have Uncle Charlie and the Chief working and sweating blood for us day and night."

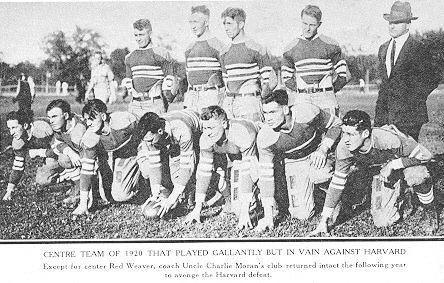

All of those factors worked together in the team's success. The 1919 season, which Centre ended with a 9-0 record and the nation's best claim to the mythical national championship, was particularly significant. In a feat unheard of for an obscure Southern college with an enrollment of 270, two men - Bo McMillin at quarterback and Red Weaver at center - were selected to Pop Warner's first string All-America team, and another player, Red Roberts, was picked for the third string.

Even more importantly, Centre defeated an excellent West Virginia team 14-6 the week before Princeton, a perennial Eastern power, lost to the West Virginians. Howard G. Reynolds, the sports editor of the Boston Post, made Centre famous in New England by running headlines in which he called Centre the "Mysterious Football Team of 1919." He and Eddie Mahan, the Harvard captain of 1915, went to Danville to scout the Colonel's talent. Centre obligingly swamped Georgetown 77-0, and, in a story almost too good to be true, Mahan discovered Moran fixing cleats in the locker room and mistook him for a trainer.

These things all made good press for Reynolds, and, as a result of the publicity, Harvard invited Centre to play at Cambridge in the 1920 season. At that time Harvard was the powerhouse of Eastern football, which was generally conceded to be the best in the nation. To recognize Centre in such a manner was to shoot the Colonels into the national limelight.

In many ways the 1920 Centre-Harvard game was a preview of the more famous 1921 contest. Though the Colonels were ahead 14-7 at one point, they were a far smaller team in size and numbers than Harvard, and they eventually succumbed, 31-14. To the New England fans, however, the Kentucky team was a source of delight. "Harvard wins, but Centre great," announced the Boston Sunday Post. Even in defeat, the Post claimed, Centre "Shows Itself Truly The Magic Team ... Kentuckians get warmest welcome ever given any team on Crimson's field."

New Englanders were particularly struck by their guests' homespun appearance. The Boston Post reported that the fans who met the Centre team at the train station greeted the players as though they were presidential candidates. To the fans surprise, the team emerged from the train dressed not in suits and ties, but in blue flannel shirts and khaki trousers ("off the fancy stuff for fair," noted the Post). Realizing that for Centre this was the game - and even the trip - of a lifetime, the crowd enthusiastically backed the Colonels every step of the way.

The casually attired Colonels may have been sharper than their hosts realized. It would not have been out of character for the Centre players deliberately to have dressed like boys from the country. Bo McMillin and Red Roberts had long since acquired the habit of trading coats with one another when the team went on trips so that each of them was dressed in ill-fitting clothing. Then, when the team arrived at its destination, Bo and Red would go to the town pool hall and, capitalizing on their poverty-stricken appearance, try to hustle the local sharks into placing large bets against Centre. The Centre players bet lavishly on themselves in Boston for both the 1920 and the 1921 games, and certainly they were calculating enough to dress unfashionably in order to get better odds.

Charmed by their guests, Bostonians entertained the team with luncheons, dances and trips to the Ziegfield Follies. That there were only 16 players on the squad further endeared them to the Eastern fans, as did the Colonels' halftime performance. The Centre players stayed on the field during halftime in accordance with habits learned in Kentucky, where locker rooms were not large enough to hold two teams. From start to finish, the Kentuckians were a dream team, and New England hearts went out to them. The Boston Post remarked,

It must have been amazing to the Danville boys to see and hear one half the enormous stadium rooting and cheering for them like mad. Every seat was sold, and hundreds of standing-room tickets disposed of .... All the news associations had their star men to furnish varied stories on the game, and metropolitan newspapers from as far west as Cincinnati had their own staff writers in the press stand.

After the game Bo tearfully refused to accept the game ball offered by Captain Horween of Harvard, promising instead to return in 1921 to win the football rightfully. Rejecting offers to play professional football, Bo turned his attention to basketball, playing forward on a Centre team that beat Harvard, Brown, and Johns Hopkins in a single week. In the spring of 1921, the governor of Kentucky named him a Kentucky Colonel, and the students of Centre "promoted" him from Colonel to Carnival King.

But neither Bo nor anyone else on the football team lost focus. The players vowed to train for the entire year until at last they could defeat Harvard. The irrepressible Red Roberts, who always looked out of shape, went so far as to go to the railroad yard in Danville the day that classes ended for the summer and demand the hardest job in the place. The team spent the summer receiving exhortations from Chief Myers. "Listen to me, old Animal Life!" he expounded in one letter to the team. "I would smoke a cigar under a gasoline shower to see you beat Harvard, and I would climb barelegged up a honey-locust tree, with a wildcat under each arm, to have you hand the same kind of dose to the rest of them."

Centre began the 1921 season by defeating Clemson, Virginia Tech, and Xavier. The team's personnel was essentially the same as in 1920, though All-American Red Weaver, who had set a record of 99 consecutive extra point kicks, left Centre to take a high school coaching position. Ed Kubale, who later coached the Colonels, replaced Weaver at the center position and proved to be an outstanding player. The play of the line as a whole was much improved by the addition of "Tiny" Thornhill as line coach.

The squad was weakened, however, when the faculty voted not to permit "Lefty" Whitnell, the team's punter and star end who had dazzled the New England fans with his touchdown reception in the 1920 game, to play because of his poor grades. Though the faculty conveniently overlooked Bo's slow academic progress - he never accumulated enough credits to graduate - it was not inclined to excuse the shortcomings of the team's lesser lights. In Whitnell's situation, the faculty minutes rather whimsically noted, "The case of Mr. Whitnell's eligibility was brought up by President Ganfield and [he] stated that in his opinion nothing could be done for him."

The faculty made itself even more unpopular as the rematch with Harvard approached by announcing that it would regard all student absences that occurred as a result of attendance at the Harvard game as unexcused. According to faculty statements, the ban was necessary because dismissing school for a football game was a violation of the regulations of the Southern Intercollegiate Association.

The town of Danville did not see the matter in quite that light. If students were not permitted to go, the town would not be able to muster the 125 passengers required to contract a special train for the trip. The Chamber of Commerce met on October 25, and, after a heated session, demanded that the College's Board of Trustees rescind the faculty ban. No results were forthcoming, leaving the Kentucky Advocate to fume bitterly that "the college should not be 'crabbed,' the spirit of the student body should not be dampened, nor should the pride of Danville be humbled in such a manner."

The team's reception in Boston was just as warm as the previous year's. Colonel Chinn reported the delight of the Eastern fans when one of the Centre players, milking his part for all it was worth, disembarked from the train and asked the Harvard manager, "Where's you boys' schoolhouse at?" Harvard was rated a 3-1 favorite and was by its own admission looking ahead to the next week's game with Princeton, but the fans were entranced with the eager team from the small Southern college. The Boston Post, trying to account for the public's fascination with the Colonels, argued that the Boston crowd supported Centre

not because they love Harvard less, but because they love Centre more. The reasons are multiple. Centre is perhaps the smallest college that ever tackled a Big Three team. Its entire football personnel is absolutely the salt of the earth. They have in their lineup an outstanding boy that transcends any star since Mahan. He is surrounded by plucky, intrepid chaps who would take broken bones for the honor to win. That is why this hostile team finds welcome in the heart of the cold codfish zone.

George Trevor of the New York Sun offered an equally romantic explanation for the Centre mystique:

... there was Uncle Charlie himself - coach, umpire, psychologist, revivalist, shoemaker, tailor and father confessor; Moran, who worked without assistants, now devising original plays, now bandaging limbs, now patching helmets, now darning jerseys; there was the 'Kentucky colonel stuff' the bands blaring 'Dixie,' the mint-julep background, the aroma of bluegrass, the Southern belles waving Gold and White pennants; there was the elemental lure of the Kentucky hills, of picturesque moonshiners, who had no connection with the college; beyond all of these was the never-failing religious appeal - the anecdotes concerning pregame prayers in the dressing room, the Centre warriors kneeling with bowed heads as they sought divine guidance.

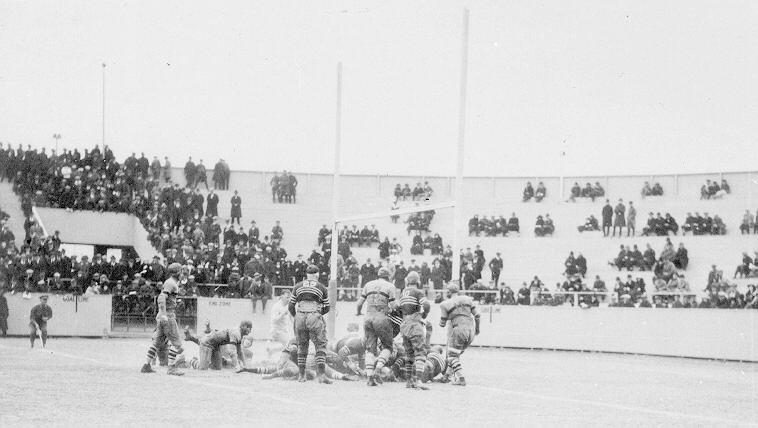

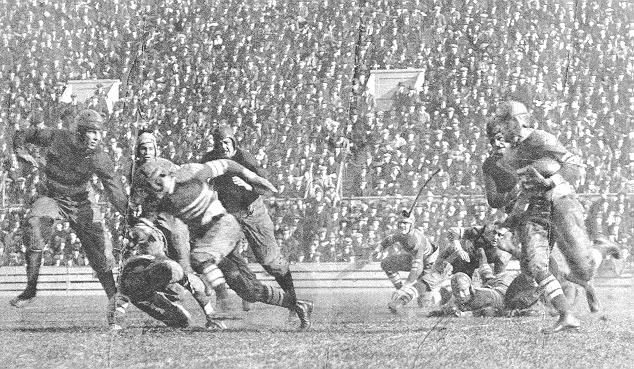

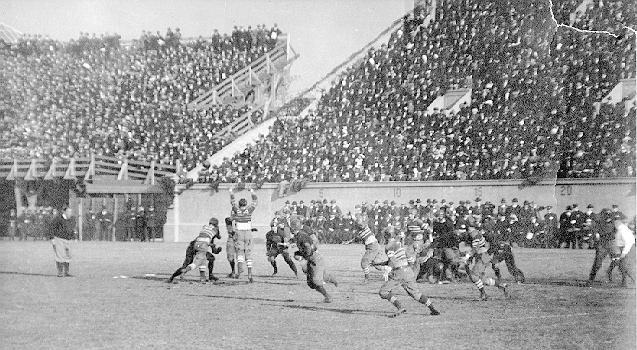

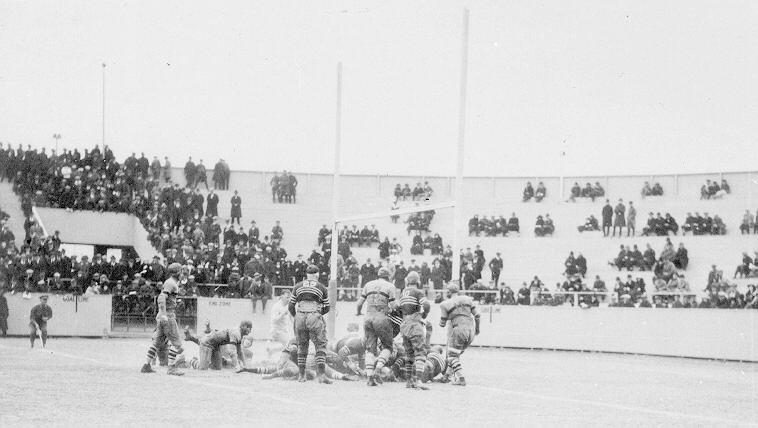

The long-anticipated rematch with Harvard was played far more conservatively than the football world had anticipated. Boston analysts predicted that Centre would fill the air with passes, but the Colonels' strategy was to avoid an open game. Anticipating the coming battle with Princeton, Harvard allowed a number of regulars not in the best of shape to sit on the bench for much of the game, but eventually all but three of the first string played. Centre's improved line and secondary were key factors on defense, as was the excellent interference that the line provided on offense. Harvard's Buell, the first string quarterback, badly missed dropkicks of 11 and 35 yards in the first half, which ended in a scoreless tie.

Halftime did not pass without entertainment. Roscoe Arbuckle Conklin Breckinridge, Centre's African-American masseur and water carrier, was accustomed to dressing up and "cake walking" for the crowd at the intermission. His performance at the Harvard game was so striking that the Kentucky Advocate of October 29, 1921, proudly reported that Roscoe's act "brought down the house." The Harvard Crimson of October 31, 1921, gave the following account of his performance: "Attired in tall silk hat with yellow vest, and just about three shades darker than any other colored man in Greater Boston, he looked like a Kentucky tobacco ad. His nimbleness in getting off and on the gridiron between plunges belied his years."

As in the case of the Centre players' homespun traveling clothes, behind Roscoe's eccentric behavior lay calculating intelligence. Fans enjoyed Roscoe as an embodiment of an Old South stereotype, but Roscoe played another function that was far more valuable to the team. In those days coaches were forbidden to send in plays from the sidelines. Roscoe used to sit on the sidelines on a bucket which had C-E-N-T-R-E spelled in large letters around it. Moran would tell Roscoe which play he wished the team to run, and Roscoe, the "communications expert extraordinary," would rotate the bucket until the letter signifying that play was facing the field where the players could see it.

Back in Danville, of course, stranded fans could neither see the game nor enjoy the halftime show. Yet several resourceful businesses in town had arranged to receive direct wires from New England, and Centre supporters found new ways to live and die with their team. For those on a limited budget, Louis Mannini announced the results free of charge in front of his news stand on Main Street, as did W. L. Lyons and Company, local Danville brokers. For the more adventurous, Stout's Theater charged 25 cents for admission, but offered attractions that could be found nowhere else in town. Here, Lefty Whitnell announced the game, and George Swinebroad, a Centre cheerleader, led cheers.

When play finally resumed after halftime, the break Centre had been waiting for came early in the third quarter. Tom Bartlett returned a Harvard punt to midfield, where Harvard was penalized 15 yards for piling on. Centre therefore had the ball on the Harvard 32-yard line. As Bo explained later, it had become apparent to the Colonels that they were in better shape than Harvard. During the first half he had carried the ball for short gains only, calling other backs' signals in order to divert Harvard's attention from him. Now, however, the time had come to run the play he had planned for weeks: the cut-in play, which Chief Myers claimed Bo ran better than any other man who ever did it.

With Red Roberts, his "human tractor," providing spectacular interference, Bo broke through the Harvard line and headed straight for the sidelines, chased closely by two Harvard backs. Without losing speed he reversed direction sharply just as he was about to go out of bounds, thus losing his defenders. He left behind the remaining men to have a shot at him, and, surviving a near fall over his own shoelace, scored the most famous touchdown in Centre College history. Bartlett missed the point after attempt, but the damage had already been done. Only once in the remainder of the game did Harvard come close to scoring, and then its gain was nullified because the Crimson team had been offside on the play. Perhaps Bo himself told the rest of the story best:

We took no more chances after that, and desperately held our six-point advantage to the end - six golden points which will always live in the history of Centre College, not just because they represented a victory over Harvard, but because those points stood for a goal that we had set ourselves, sacrificed for, and achieved.

Every man more than played his part. Roberts and Tanner, Snoddy and Armstrong, all covered themselves with glory in the backfield, while Bartlett and Jones, Kubale and Shadoan and all of our husky linemen proved themselves heroes. No better blockers ever played football!Danville Goes Mad

The end of the game was just the beginning of the bedlam which was to follow. Ten thousand fans engulfed the Centre team and carried Bo off on their shoulders. Cheering crowds lined the streets as the team rode back to its hotel. For the general public, Centre's victory was a heroic act of almost metaphysical proportions: it was the triumph of a poor small group over a large rich one; it was the American dream come true; it was David over Goliath.

In Danville, Centre's win plunged people into joyous exuberance. "Danville Goes Mad," headlined the Boston Post. "Hysteria, madness, insanity, none of these words do justice to the malady with which this town was stricken late this afternoon." The Post proceeded to describe a Danville barely recognizable to generations of Centre students who have both loved and laughed at its sedateness:

Picture a fire department running wildly around in the rain with no place to go, but going just the same. Imagine hundreds of students and former students, bald headed men, women, girls and youngsters parading up and down the streets, yelling and crying and laughing. Here a painted cow with a demented college boy on its back, there a baby bawling its head off. Automobiles and trucks wandering aimlessly to and fro, overloaded with raving humans.

On every store window, every sidewalk, in the streets, on back of coats, appeared white figures, '6 to O.'And to this the chorus of human shouts, the bedlam of factory whistles, church, school, and courthouse bells, overworked automobile horns and then there's no use trying to describe it, but there you have a faint picture of how Danville celebrated tonight.For the Centre players riding home on the train to Danville, the victory meant money as well as joy. The year before they had bet on themselves and lost everything. This year Bo had sent Gus King, a student, up to Harvard a week before the game in order to scalp tickets and bet the money on the game. Earl Ruby of the Courier-Journal reported that "Bo had more folding money on the night of Oct. 29, 1921, in a lower berth on a Pullman heading back to Kentucky than could normally be found in a lot of small town banks." Colonel Chinn recalled that he had never seen so much money in one pile as he saw that night. If the players thought after looking at all that money that they had seen everything, however, they had yet to see the heights to which a frenzied Danville could aspire.

The entire town, plus the Governor of Kentucky and the Superintendent of Public Education, met the players at the station. The team was hustled into the town's fire engine to begin a parade in which most of the citizens joined. Led by Roscoe, the parade included bands, goats dressed to represent Centre and Harvard, a battered old Ford representing Harvard, a man dressed like "Old John Harvard," cars decorated gold and white, and hundreds of other cars, all blowing their horns, followed by thousands of people on foot. The triumphal procession ended at the town courthouse, which became the site of innumerable speeches.

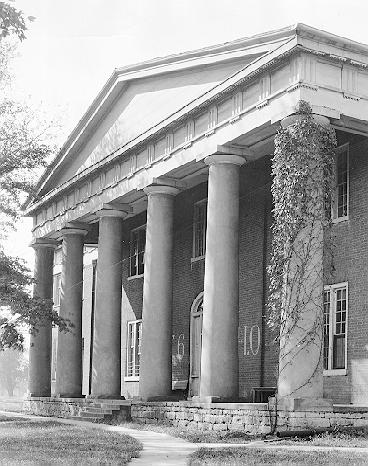

Everywhere, plastered over every building, was the jubilant C6-HO, Centre's "poison formula" for victory. There was even a cow running loose, painted green, with C6-HO on its side to proclaim the results of the game. The town, in short, was in utter pandemonium. Even today, sharp-eyed observers can discover in Danville signs of that celebration. Until its recent renovation, the C6-HO on the front of Old Centre was, though painted over, still visible; and buildings near the rail yard may still be found that bear the C6-HO mark.

When the day of jubilation had ended, the Centre players turned their attention back to football, for the season was far from over. Shutting out the next four teams it played, Centre finished the regular season undefeated and found itself inundated by offers for post-season appearances. Unbelievable as it seems today, Knute Rockne traveled to Danville's Busy Bee Cafe that fall to ask Moran to play Notre Dame at Soldier Field in Chicago. just as Moran had to refuse bids from the Polo Grounds, the University of Detroit, Yale and Princeton, and the Rose Bowl, so he had to decline Notre Dame's offer as well, for Centre had already scheduled several postseason games.

The Colonels defeated Tulane 21-0 on Thanksgiving Day in New Orleans and Arizona State 38-0 on December 26 in San Diego. Their last game was in Dallas on January 2 against Texas A&M In the morning, the team watched Bo marry his Fort Worth high school sweetheart. In the afternoon, with his wife Marie on his arm, Bo led his teammates on to the field to battle the A&M

Aggies.

The end of the season marked the beginning of the end of an era. Bo would go on to a distinguished coaching career, defeating Harvard again as coach of tiny Geneva College, and bringing Indiana University its first Big Ten championship. But Centre's teams, within a few years of his departure, were no longer able to compete with teams of national championship caliber. Gradually the determination to play and defeat the premier teams in the nation lapsed into dreams and memories.

The year after Bo's premature death from cancer in 1952, Centre added to its campus a McMillin Memorial Room, marked by a large portrait of Bo in his college uniform. With later renovations to athletic facilities, however, the McMillin Room disappeared, leaving the campus with no visible reminder of its most revered athlete. Even the game ball from the 1921 Harvard game has vanished. Bo could never bring himself to part with it, insisting that, rather than give the ball to the College, he would pass it on to his children. Presumably he did, for the most famous artifact in Centre history resides nowhere on its campus.

Thus over the years, the glory days of 1921 have gradually faded away. Many things at Centre have changed since 1921 - often for the better. Women and African-Americans are now full members of the College community, not just sideline observers. The faculty makes equal academic demands of all students. No one, not even a star quarterback, would be permitted to remain at the College without making satisfactory progress toward graduation. Centre is proud to be a Division III college - a school where the scholar athlete is the norm, not the exception. No one receives scholarships to participate in athletics at Centre anymore.

And yet. And yet the memory lingers on, a tribute to a time when teams from Ivy League schools and small Southern colleges were the powerhouses of the nation. In the fall, when the wind blows with a chill, and the leaves blaze red and orange, we of Centre return to campus, and we remember. We remember past glories, we hum the Centre Fight Song, and we continue the proud tradition. For our legacy is also our future. Our teams still give their all on the field. And in the classroom, the lab, and the workplace, our faculty, students, and alumni continue to win honors all out of proportion to our small numbers. From our hearts, year after year, we return Centre's loyalty to us by placing Centre first in the nation in the percentage of alumni donations.

Professor Newhall noted in his 1994 commencement address at Centre that all the College's graduates put together would not come close to filling Rupp Arena. As in 1921, so today we remain a small group, dwarfed by larger neighbors. And yet, we who have found here a community that shaped and challenged us to become "Centre people" remain true to our history. To come from a small college and to do it proud; to put it on the academic map time and time again; to go to Ivy League graduate schools and hear people say with respect, "Oh, you went to Centre"; to become civic leaders of vision and compassion - this is our tradition, this is our legacy, this is the 1921 celebration that has not abated.